African Americans and the History of "Human Rights"

While the concept of “human rights” figures prominently in the domestic policy and public life of many nations around the world, history reveals that the United States took a decidedly different path. As historian Carol Anderson details in her book Eyes Off the Prize (2003), the nation’s use of the concept reflects its history of racism—one in which narrower notions of “civil rights” gained currency in domestic affairs over and against the broader conceptions of “human rights” that remain central to the nation’s foreign policy. Having observed the inability of the U.S. government to uphold even the “civil rights” ostensibly guaranteed to them by the U.S. Constitution and legislation, a series of African American leaders have nevertheless invoked the language of “human rights” to underscore the urgency of their situation on the international stage. These figures—including W.E.B. DuBois, William Patterson, Malcolm X, and Tommie Smith—have played vital roles in an underacknowledged story of Black people leading global antiracist movements while also pushing their own country to be better. Moreover, this multigenerational story of vision, persistence, and recurring difficulty brings the historic significance of the recently announced United Nations investigation into human rights abuses against Black people around the world into sharper focus.

In 1947, W.E.B. DuBois submitted a letter to the newly founded United Nations titled “An Appeal to the World: A Statement of Denial of Human Rights to Minorities in the Case of Citizens of Negro Descent in the United States of America and an Appeal to the United Nations for Redress.” There, he called upon the international community to acknowledge and intervene in the racial violence that continued to permeate the United States, and affirm the fundamental human rights of African Americans. He also implored his own nation’s leaders to consider how they could imagine themselves leading the free world in rights and equality while continuing to uphold racial inequality and violence. DuBois’ hopes of bringing the nation’s human rights abuses to the United Nations for intervention would not be realized, however, due to a host of factors that prompted U.N Commission on Human Rights Chair Eleanor Roosevelt to prioritize the Cold War era-fight against the Soviet Union over the domestic fight against racism. Any indictment of the U.S. made on the international stage, she thought, would be readily appropriated by the Soviets and ultimately threaten her broader political project. Despite this devastating failure for DuBois, his work laid the groundwork for yet another attempt at international redress.

In 1951, the Civil Rights Congress (CRC) would issue a petition to the United Nations titled “We Charge Genocide” that recounted 152 instances of the murder of unarmed Black people by police and lynch mobs. The 200+ page petition argued that the U.S. was in violation of the U.N. Genocide Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of Genocide which was held in the aftermath of the Holocaust in 1948. Further, the CRC argued that the U.S. government failed to act in accordance with both international law and its own Constitutional mandates, and must therefore face the penalties assigned to all nations guilty of genocide. CRC activist William Patterson would deliver the petition to the U.N. in Paris in 1951 but an investigation into the U.S. would not proceed and Patterson’s passport was subsequently revoked.

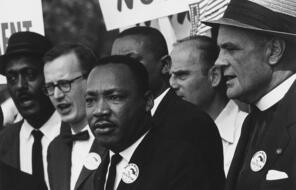

Not a decade later, Malcolm X would depart the Nation of Islam and travel to Africa where he issued a related appeal to the human rights of African Americans. During the second meeting of the Organization of African Unity in Cairo, Egypt in 1964, X would urge African leaders to notify the United Nations of ongoing and unchecked human rights abuses in the U.S. There he explained that his aim was to “elevate our freedom struggle above the domestic level of civil rights.” Though X would persuade one African nation to answer his cry, his work on the global stage would be foreshortened when he was assassinated a year later and the U.S. would not be charged with human rights abuses as he envisioned. Despite this immense loss, Black mobilization under the banner of human rights would continue.

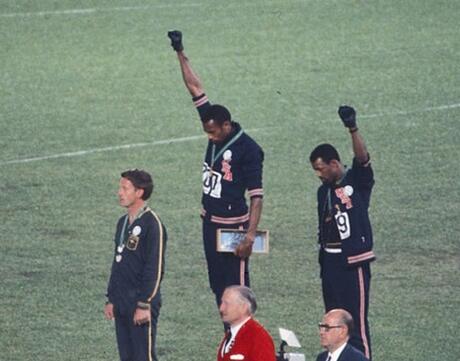

One highly visible manifestation of this fight surfaced a few years later at the 1968 Olympics in Mexico City where Black medalists Tommie Smith and John Carlos staged their iconic Black Power salute. Together with Black sociologist Harry Edwards and other Black athletes, they formed the Olympic Project for Human Rights (OPHR) which assembled to boycott the olympic games due to racism. OPHR had grown out of the organizing work of Edwards and collaborator Kenneth Noel at San Jose State University where their work led to the first major college in the country canceling an athletic event to avoid racial protest. The work of Edwards, Smith, and Carlos are echoed by the contemporary human rights activism of former San Francisco 49ers quarterback Colin Kaepernick who electrified the nation when he knelt during the national anthem to protest police brutality and racial violence in 2016. And though the resulting #TakeAKnee movement provoked heightened discussion of anti-Black racism and violence, the core question of how the U.S. government, its police forces, and its citizens are held accountable to these values remains.

Facing History invites educators to use our teaching unit on the Universal Declaration of Human Rights in the classroom.

In July 2021, an incredibly momentous development took place, however. The United Nations announced that, finally, it will “set up a panel of experts to investigate systemic racism in policing against people of African descent.” A panel of three experts has been tasked with uncovering the drivers and consequences of systemic racism in policing, including the legacies of slavery and colonialism, and to make policy recommendations. This decision emerged from a resolution by African countries that built on a U.N. report that analyzed the deaths of 190 Black people, mostly in the U.S., “detailing the lack of accountability for police killings and urging states to pursue change.” The panel is tasked with investigating law enforcement across the world, but references to the murder of George Floyd have provoked hope that the U.S. context will figure prominently in the investigation.

In response, the Biden Administration announced that they would “issue a standing invitation to all U.N. envoys.” Secretary of State Antony Blinken described their move by explaining that the United States must "face the realities of racism and hatred at home" before trying to be a "credible force for human rights" internationally. In a marked reversal of Roosevelt’s midcentury decision to sideline attempts at protecting human rights for African Americans to prioritize another political struggle, these recent events suggest that at least some American leaders are beginning to grasp the urgency of protecting human rights for African Americans, and are incorporating it into their broader vision for global politics.

Don't miss out!

- download classroom materials

- view on-demand professional learning

- and more...