Continuing Lemkin's Legacy: What Can We Do to Prevent and Stop Genocide?

At a Glance

Language

English — USSubject

- History

- Social Studies

Grade

9–12Duration

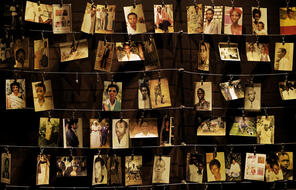

One 50-min class period- Genocide

Overview

About This Lesson

Raphael Lemkin was instrumental in the drafting and the adoption of the United Nations Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide. With the ratification of this treaty, Raphael Lemkin's original goal was realized. Now there was an international law that nations could draw on to prosecute and punish perpetrators of genocide; now leaders like Mehmed Talaat could be brought to trial in International Criminal Court and men like Soghomon Tehlirian might not feel compelled to take justice into their own hands.

Yet, since the Genocide Convention was adopted in 1948, genocides have continued around the world. Activists, such as Rebecca Hamilton, continue the struggle for genocide prevention that Lemkin began in the 1920s. While Lemkin worked to create a law when one did not exist, today's activists focus on pressuring politicians to use this law as a means and prevent genocide.

Preparing to Teach

Lesson Plan

Activities

Assessment

Extension Activities

Materials and Downloads

Continuing Lemkin's Legacy: What Can We Do to Prevent and Stop Genocide?

Unlimited Access to Learning. More Added Every Month.

Facing History & Ourselves is designed for educators who want to help students explore identity, think critically, grow emotionally, act ethically, and participate in civic life. It’s hard work, so we’ve developed some go-to professional learning opportunities to help you along the way.

Exploring ELA Text Selection with Julia Torres

On-Demand

Working for Justice, Equity and Civic Agency in Our Schools: A Conversation with Clint Smith

On-Demand

Centering Student Voices to Build Community and Agency

On-Demand