My name is Arn Chorn-Pond. When I was a child, war came to my country, Cambodia. Soldier forced me to play propaganda song for them. If I don't play the flute, the music for them, I would have died or they would have killed me.

That boy was me 20 years ago.

So it's good now to come back and talk to you guys again here. You could be my classmate like what, 20 years ago? It's after only one week that we settle in White Mountain home. My dad took me here. Three of us here and walk in this entrance. Three of us, very cold, I remember it. And we walked in and I felt very scared about, you know? Right away, I hear the noise. I heard the noise coming and all that. So many kids, you know? I'm blank. I have almost nothing beside knowing bathroom, rice, those three or four words that I had in my head from the refugees camp.

I know that it's just a school. But I don't know what they want to do with me. I never had school in my life before the Khmer Rouge in '75. After they found out that I can run well and all of that, they decide to put me in soccer. I think I scored every game or something. We became like state championships two years or three years on the row. Before like, I'm nobody. And then they start notice us. They start, like, you know, they come and pay attention to us.

The other team would trying to hit me and make fun and make fun face. In the jungle, if somebody do that to me, I shoot them. You know? That's what the Khmer Rouge taught me. You know? If somebody stare at you, they don't have to make face like that, I shoot them. I was really happy and proud of myself that I didn't do it, even though they hit me, and I didn't hit them back. In the court and even outside of the court.

American kids are good in sort of like making fun. Sometimes not bad intention. You know, they come and put their, you know, like, their head or their arms, their hand on my head. They could play around. They go bang, bang, bang, bang, bang. And say, Arn, Arn, Arn. They put my name and they laughed a little bit. Cambodian people protecting their heads a lot. Their parent told them that there Buddha on your head. So nobody play with your head. You know? And the kids here did not know.

I don't think the American kids, American students who were my classmate know anything about where I came from, first of all, and what I went through. So it hurts very hurtful for me. That I felt like nobody was on my side or something, you know? And that's enough for just get me crazy. There are some of the kids who really want to reach out to me. But the big problem was the language.

Things were different when I began to learn some English. I have my ESL teacher, who really worked things really hard. She knew that I had something bottling up inside, and maybe about to explode. And she just, Arn, you know, learn fast. I can see it in her eyes, you know? With her, I start learning to write. And then my first speech, I think, at John the Divine church. And that was a big thing for me and for us.

Yeah. That was really a kind of, you know, turning point for me to like, say, yeah. I can speak now. And people liked what I said. In that church, was, you know, like, you can hear a pin drop there, you know? And I cried, I think, that day. Because, you know, I felt like, you had power. You had some power just learning how to speak English. You know?

This time is very different from having power with the guns. But I feel power just standing there and talk for the first time how I really felt inside.

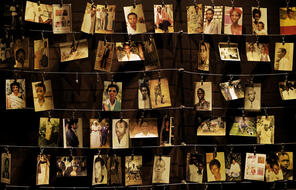

And I'm from Cambodia. And in 1975, when the Khmer Rouge took over Cambodia, the whole country were happy and cheering. Five days later, the Khmer Rouge announce that we have to leave the city, 100,000 people. And they said we are going to work now. And they have guns.

They asked us to work to wake up at 4 o'clock to go to planting rice. They don't let us have food to eat. Everybody dying. And work at night too. To 12 o'clock. And sometime, no food for two weeks. And they also start killing people are dying on the field, especially children die on the field. They're starving to death.

And after that, they separate us. And I was taken away also from my sister and my mother. I was sent to one place called Wat Ek where 500 kids were there with me. That was a execution place. The place where they kill people every day. Most of the time, they ask us to watch. And again, I was forced, when I wasn't 12 years old to fight against the Vietnamese by the very people who kill my family.

And after a while, I live in a jungle, I end up in Thailand where I met my father, my foster father, who worked for the UN in the camp in Thailand.

As a child, I've never-- I don't-- I've never imagined there are good people in the world. I got it that I need to involve young American kids to know about what I went through. And it's just a reflection of each other, you know? They need to know about me. I need to know about them. We all didn't know about each other. And the people who next to you. You didn't even notice them because we are too busy, you know?

I was sitting next to a boy, he's a white boy. Didn't-- sometimes they didn't notice me that I have a story to share. I didn't know that he has a story to share either. So we didn't share. Most important your own story. It's not only mine. The resources you have here, the love you have here, the freedom you have here, that's a good thing. And don't take it for granted. So go out. Fly around the world and save the world.

[FLUTE]