Race and Belonging in Colonial America: The Story of Anthony Johnson

At a Glance

Language

English — USSubject

- History

- Democracy & Civic Engagement

- Human & Civil Rights

- Racism

Special Note

White Supremacist groups have claimed that Anthony Johnson, a Black forced laborer who became free in 17th century Virginia, was the first legal slave owner in the British colonies that became the United States. That claim is historically false and misleading. It is important to note the following regarding Johnson’s life and the beginnings of slavery:

- The development of the institution of slavery in North America was complex. In the 17th century, the enslavement of Africans co-existed with indentured servitude, and laws governing both were in flux.

- Anthony Johnson was, himself, enslaved by an English settler upon being brought to North America.

- When Johnson was brought to North America, status and power in colonial Virginia society depended much more heavily on one’s religion or whether one owned property than it did on skin color or a notion of race.

- For a period of time in the 17th century, some of the enslaved, like Johnson, were able to gain their freedom, own land, and have servants.

- By the end of the 17th century, however, colonies began to make legal distinctions based on racial categories; the legal status of Black people deteriorated while the rights of white European Americans increased. Johnson’s descendants, who were classified as Black, were stripped of the property they inherited from him.

- A system of slavery in which enslavement was lifelong, hereditary, and based solely on race was established in the colonies in the beginning of the 18th century.

Why are White Supremacists making these claims? They are doing this for several reasons, including to promote denial of the history of chattel slavery and its impact, particularly on Black Americans. For more information, see the following articles:

- The Curious History of Anthony Johnson: From Captive African to Right-wing Talking Point by Tyler Parry

- Slavery Myths Debunked by Jamelle Bouie and Rebecca Onion

Introduction

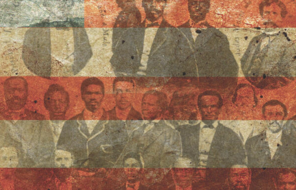

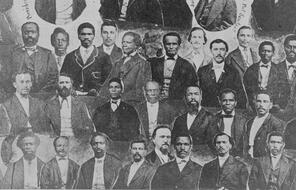

For at least 400 years, a theory of “race” has been a lens through which many individuals, leaders, and nations have determined who belongs and who does not. The theory is based on the belief that humankind is divided into distinct “races” and that the existence of these races is proven by scientific evidence. Most biologists and geneticists today strongly disagree with this claim. Some historians who have studied the evolution of race and racism trace much of contemporary “racial thinking” to the early years of slavery in the colony of Virginia, in what is now the United States.

When the first Africans were brought to Virginia in 1619, status and power in the colony depended much more heavily on one’s religion or whether one owned property than it did on skin color or any notion of race. Enslaved Africans, enslaved Native Americans, and European indentured servants labored in Virginia tobacco fields. Indentured servants agreed to work for a planter for a specific period of time in exchange for their passage to the New World, and then they often became free. The enslaved, either Native Americans or Africans forced to come to North America, were also sometimes able to gain their freedom. But this would soon change, as indentured servitude became less common and a system of slavery took hold in the English colonies in which enslavement was for life and only people of African descent were enslaved.

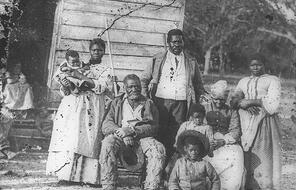

The story of one man, Anthony Johnson, helps illustrate the changes in Virginia society that laid the foundation for the institution of race-based slavery that thrived until the Civil War. Johnson was brought to Virginia, enslaved by an English settler, in 1622. He was able to earn his freedom, own land, and have servants of his own, but his descendants would not be permitted to do any of these things. Charles Johnson and Patricia Smith tell Johnson’s story.

Part One

Antonio may have arrived at the colony from Angola [Africa] the year before aboard the James. Sold into bondage to toil in the tobacco fields, “Antonio, a Negro” is listed as a “servant” in the 1625 census. Virginia had no rules for slaves. So it was possible that Antonio knew hope. Perhaps he felt that redemption was possible, that opportunities existed for him even as a servant . . .

“Mary a Negro woman” had sailed to the New World aboard the Margrett and John. Soon she became Antonio’s wife.

“Antonio the Negro” became the landowner Anthony Johnson . . .

Although it is not known exactly how or when the Johnsons became free, court records in 1641 indicate that Anthony was master to a Black servant, John Casor. During that time, the couple lived on a comfortable but modest estate and Anthony began raising livestock. In 1645, a man identified as “Anthony the Negro” stated in court records, “Now I know myne owne ground and I will work when I please and play when I please.”

It cannot be proved that it was actually Anthony Johnson who spoke those words. But if he did not speak them, he felt them, felt them as surely as he felt the land beneath his feet. The words didn’t reflect his state of ownership as much as they reflected his state of mind. He owned land. He could till the soil whenever he wished and plant whatever he wished, sell the land to someone else, let it lie fallow, walk away from its troubles. He could sit in his house—his house—and ignore the land altogether. Anthony was a man in control of his own.

Comprehension Questions

- In the census documents and court records described in this passage, how is Anthony identified? Does the way he is described appear to have any consequences so far in his story?

- What detail suggests to historians that Anthony became free in 1641 or before?

- According to the authors, what did Anthony think it means to be free? What are the benefits of freedom?

Part Two

By 1650, the Johnsons owned 250 acres of land stretched along the Pungoteague Creek on the eastern shore of Virginia, acquired through the headright system, which allowed planters to claim acreage for each servant brought to the colony. Anthony claimed five headrights . . .

No matter how he amassed his acreage, Anthony’s “owne ground” was now formidable.

The couple was living a seventeenth-century version of the American dream. Anthony and Mary had no reason not to believe in a system that certainly seemed to be working for them, a system that equated ownership with achievement. If not for the color of their skin, they could have been English.

Very few people who had inked their signatures on indenture forms received the promise of those contracts. At the end of their periods of servitude, many were denied the land they needed to begin their lives again. Anthony Johnson was one of a select few able to consider a piece of the world his own.

In 1653, a consuming blaze swept through the Johnson plantation. After the fire, court justices stated that the Johnsons “have bine inhabitants in Virginia above thirty years” and were respected for their “hard labor and known service.” When the couple requested relief, the court agreed to exempt Mary and the couple’s two daughters from county taxation for the rest of their lives. This not only helped Anthony save money to rebuild, it was in direct defiance of a statute that required all free Negro men and women to pay taxes.

The following year, white planter Robert Parker secured the freedom of Anthony Johnson’s servant John Casor, who had convinced Parker and his brother George that he was an illegally detained indentured servant. Anthony later fought the decision. After lengthy court proceedings, Casor was returned to the Johnson family in 1655.

These two favorable and quite public decisions speak volumes about Anthony’s standing in Northampton County. The very fact that Johnson, a Negro, was allowed to testify in court attests to his position in the community. In the case of the community benevolence following the fire, the fact that Anthony was a Negro never really seemed part of the picture. He was a capable planter, a good neighbor, and a dedicated family man who deserved a break after his fiery misfortune. In the case of his legal battle for Casor, Anthony’s vision of property and the value accorded it mirrored that of his white neighbors and the gentlemen of the court. Anthony Johnson had learned to work the system. It was a system that seemed to work for him ...

Comprehension Questions

- Based on what the authors imply, what did an inhabitant of Virginia need in order to be considered English?

- What phrase in the third paragraph best summarizes what the authors mean by “a seventeenth-century version of the American dream”?

- What evidence can you find in this passage that suggests whether or not the Johnsons were part of Virginia’s universe of obligation?

Part Three

[I]n the spring of 1670 . . . “Antonio, a Negro”—respected because he had managed to live so long on his own terms—met the end of his life. He was still a free man when the shackles binding him to this world were unlocked.

. . . In August of that year, however, an all-white jury ruled that Anthony’s original land in Virginia could be seized [from his surviving family] by the state “because he was a Negroe and by consequence an alien.” And fifty acres that Anthony had given to his son Richard wound up in the hands of wealthy white neighbor George Parker. It didn’t matter that Richard, a free man, had lived on the land with his wife and children for five years.

The “hard labor and knowne service” that had served the family so well in the New World was now secondary to the color of their skin. The world that allowed captive slave “Antonio, a Negro,” to grow confident as Anthony Johnson, landowner and freeman, ceased to exist. The Virginians no longer needed to lure workers to their plantations. Now they could buy them and chain them there. 1

Comprehension Questions

- Were the Johnsons included within Virginia’s universe of obligation after Anthony’s death? What evidence from this passage supports your answer?

- According to Virginia officials, what did it mean to be a “Negro” in the 1670s? How is this meaning different from the meaning that prevailed earlier in Anthony’s life?

- According to the last paragraph, how did the criteria by which Anthony’s status in Virginia society was judged change?

- 1Excerpted from Charles Johnson and Patricia Smith, Africans in America: America’s Journey through Slavery (San Diego: Harcourt & Brace, 1999), 37–43.

How to Cite This Reading

Facing History & Ourselves, "Race and Belonging in Colonial America: The Story of Anthony Johnson," last updated March 14, 2016.

This reading contains quoted text not authored by Facing History & Ourselves. See footnotes for source information.