Breadcrumb

This resource is part of:

Sonia Weitz

At a Glance

Language

English — USSubject

- History

- The Holocaust

Sonia Weitz passed away on June 23, 2010. We mourn the loss of our longtime friend. She was a Holocaust survivor, a poet, and an inspiration to so many teachers and students. We will miss her beauty, grace, and kindness. Her poetry is read in Facing History classrooms across the world. See the eulogy by Rabbi David Klatzker of Temple Ner Tamid, Peabody, Massachusetts.

Sonia Schreiber Weitz was born in 1928 in Krakow, Poland, where she lived a "modest but comfortable" life in the Jewish section of the city. Her mother, Adela Finder Schreiber, was a dedicated housewife and her father, Janek (Jacob) Schreiber, was a middle-class businessman who owned a small leather goods shop. Sonia was only eleven when the Germans invaded Poland.

In 1941, Sonia and her family were forced to enter the Kraków ghetto. Her mother was taken from the ghetto and sent to the Belzec death camp, where she was killed. In 1943, Sonia, her older sister Blanca, and their father, were sent to Plaszów, a slave labor camp south of Kraków. Though she still had Blanca at her side, Sonia was separated from her father in the camp. In December, 1944, the two sisters were transferred to Auschwitz. They would never see their father again. Sonia and Blanca were forced to march across Poland and Germany to Bergen-Belsen. They were transported in cattle cars to Venusberg and ultimately, Mauthausen, where after years of suffering, they were liberated in May of 1945 by American troops. Having Blanca by her side throughout the horrific experiences of the Holocaust was crucial to Sonia's survival. Blanca would ultimately serve as a role model and mother figure in Sonia's life.

Sonia and Blanca are the only two surviving members of her entire family. For three years Sonia lived in displaced persons camps across Austria. It is during this period that Sonia wrote many of the poems found in I Promised I Would Tell, her poetic memoir of her experiences in the Holocaust. She moved to Peabody, Massachusetts in 1948 with Blanca and Blanca's husband, Norbert. Sonia later married Dr. Mark Weitz and raised a family. Always an activist, she founded the Holocaust Center Boston North with Harriet Tarnor Wacks in 1981. Today, Sonia touches thousands of students through her book and her speaking engagements. I Promised I Would Tell is used in classrooms all over the world, from the U.S. to China and Pakistan. She has begun a new initiative, the Holocaust Legacy Partners project, so that survivor testimony will never be lost.

Explore Videos

Hear Sonia Weitz speak about her life and read her poetry in the following videos.

As a survivor of the Holocaust, I come from another world. I come from a universe where my people were condemned to torture and to death for no other reason but because they were Jewish. Of course, not all the victims were Jewish, but all the Jews were victims. My first poem will hopefully make the other world a little more real for you.

Come, take this giant leap with me / into the other world... the other place / where language fails and imagery defies, / denies men's consciousness and dies upon the altar of insanity. / Come, take this giant leap with me / into the other world... the other place, / and trace the eclipse of humanity... / where children burned while mankind stood by, / and the universe has yet to learn why.

What I am saying is that normal standards don't apply to the Holocaust, that it is unspeakable and unthinkable. In fact, the Holocaust is a crime without a language. I want to speak about my experiences during the Holocaust. I survived five Nazi camps and the Kraków Ghetto.

But first, a few words about my early childhood. I was born in Kraków in Poland. I lived with my parents and with my only sister, with whom I survived. Again, that's a miracle that the two of us survived. But when you consider that in a family of-- well, we stopped counting at 84. Out of 84, only my sister and I survived. So, of course, it's not a miracle, it's a tragedy.

My early childhood was very normal, very uneventful. I was pampered and protected like any little girl. I have wonderful memories of my grandmother. And, in fact, I brought a photograph with me, today, of my grandmother and just three of her many children. My mother is in that photograph sitting on the floor. She's, perhaps, a year and a half old. The summer months that we would spend on the farm were wonderful. My memory of picking mushrooms and berries and a wonderful smell of fresh baking bread.

The other memories that always come back to me when I speak about my early childhood is when I remember my parents and other members, aunts and uncles, would talk about trying to get out of Europe. Now, getting out meant that you had to have someone who was willing to take you in, perhaps in the United States. There were very strict immigration laws. We could not go to Palestine because the British would not allow any numbers of Jews to come in. In fact, in '39, they literally closed the doors to the Jewish people who were trying to get out.

And so there was no place for us to go. And no matter how my parents and the other members of my family tried to figure a way out, there just wasn't any. And so we were trapped. And we were slaughtered. For me, the beginning of the end starts in 1939 with the invasion of Poland. The Nazis marched into Poland in September 1939. In fact, they marched in on the 1st of September and by the 6th, in six days, they took my city, Kraków, and immediately the early persecutions began.

We had to wear the armband with the Star of David. There was forced labor. My father's business was taken away, so there was no money coming in. There was this incredible secret wedding, my sister marrying Norbert in a cellar. It's a moment I'll never forget.

The very first victim in my family was an uncle of mine who was arrested together with the leadership of his city, my uncle Henryk. And he was taken to Auschwitz before it became a real death factory. He was killed and his ashes were sent to my aunt. This was the first time I saw my father cry. And, of course, it would not be the last. Very shortly after the invasion, I remember leaving Kraków for a little while, in fact, we went to the city of Tarnów where most of my family were killed. Most members of my family were rounded up in the square and shot. Others were taken at different times and killed.

My first memories of the Kraków Ghetto are of a wall going up around a small section of the city and the Jews were herded in. The Kraków Ghetto was pretty much like every ghetto you've ever seen in documentaries only smaller, let's say, than Warsaw.

Conditions were horrific. There was hunger. There was death. We were terribly crowded. I remember living, perhaps three, four families to a room. And we would hang blankets from the ceiling just to have some sort of privacy.

They started taking away-- now, of course, we didn't know at the time that these people were destined for death-- but they started taking away, rounding up, the old, the sick, and the children. Old was anyone 50, 55, perhaps. The sick were anybody who was either physically or mentally handicapped. And then the children. Children under 14 were transported out.

We, of course, didn't know what was happening to them. But somehow my parents managed to-- I was in trouble because I wasn't 14-- and so they managed to get me false papers, which claimed that I was 14. And so we begin to cheat. I cheated a lot. Later, I cheated with my sister. I made myself older. She made herself younger.

At one point, I cheated by getting a document, somehow-- my parents never told me how this was done, because they were always afraid that, was I caught and tortured, I would have probably told how I got it and endangered other people. So I have no idea how this was done. But one time, they managed to get me papers which would allow me to get out of the ghetto with Aryan papers claiming that I was not Jewish. My mother even dyed my hair blonde.

And so we cheated in many ways. Temporarily, I was safe because I was cheating and had the papers that I was 14. However, the lists were growing constantly. And one day my mother was on the list to be evacuated, to be sent out of the ghetto. And the transports were going constantly. And there's that one horrific night when my mother was taken away from us.

I always find it very difficult to talk about it, so perhaps I'll read just part of a poem which I wrote in my diary that night in the ghetto. Later on, of course, we were not allowed to even have paper or pencil and I would remember my poems in my head. And eventually, after the war, I wrote them down in Polish and then finally, finally into English. This is part of that poem which I wrote that very night when my mother was taken.

I suffered, but / I didn't cry: / The pain, so fierce, so deep... / It pierced my heart / And squeezed it dry. / And then, I fell asleep. / Asleep in agony / And dreams... / A nightmare that was true... / I heard the shots, / The screams that came / From us, from me and you. / I promised I would / Tell the world... / But where to find the words / To speak of / Innocence and love, And tell how much it hurts... / About those faces / Weak and pale, / Those dizzy eyes around, / Six million lips / That whispered "help" / But never made a sound... / To tell about / The loss... the grief / The dread of death and cold, / Of wickedness / And misery... / O no!... it can't be told."

My mother was taken to Bełżec. Bełżec was one of the six death camps in Poland. And, of course, we never saw her again.

Soon my sister and I, Blanca and I, Norbert, her husband, and my father were taken to our first camp. The very first camp was Płaszów. Płaszów was not an extermination camp, for lack of better words. Truly, there is such a lack of words in this piece of history.

What I mean by saying not an extermination camp is that we didn't have any crematoria and there were no gas chambers. But there was a hill where people were stripped of their clothing, they were shot, they were dropped into a ravine, and their bodies were burned. It was a pretty awful place. There were hangings. There were lots of public hangings. I have a long poem about the hanging of a young boy and an old man. The young boy was hanged because he sang the Russian song. And so the punishment is just something that is mind-boggling.

There were dogs that would tear people apart. We had a commandant who was a real monster. He would come inspecting us at work. One time when I was digging ditches and building the road from the Jewish stones of the Jewish cemetery on which the camp was built. We were breaking up the stones, and he came by and didn't like the way my friend's mother was working, so he took out a gun and shot her.

He would order prisoners to run and he would shoot for target practice. It was a pretty, pretty awful place. We had all kinds of floggings, all kinds of public punishment. But I was with my sister and I was with her all the time. And being with her was a great comfort. And, of course, this was not a camp that was as bad-- and everything is so relative and there's such a lack of words-- it was not as high security either, not as high security as, for instance, Auschwitz or Bergen-Belsen.

And I want to share another poem with you, which makes me feel a little better. It's a poem about my father. My father and Norbert were in the men's part of the camp. My sister and I together in the women's part. And I sneaked in to see my father one day. And there was a boy, probably also cheating about his age, playing a harmonica.

And you already have an idea how dangerous it was to have anything personal because of that boy who was hanged when he sang a Russian song. But still, he hung on to that very precious thing that he had and he played his harmonica. And my father looked at me and said, "You and I never had a chance to dance together." And I call this poem "Victory."

I danced with you that one time only. / How sad you were, how tired, lonely... / You knew that they would "take" you soon... / So when your bunk-mate played a tune / You whispered: "little one, let us dance, We may not have another chance." / To grasp this moment... sense the mood; / Your arms around me felt so good... / The ugly barracks disappeared / There was no hunger... and no fear. / Oh, what a sight, just you and I, / My lovely father (once big and strong) / And me, a child... condemned to die. / I thought: how long / before the song / must end / There are no tools / to measure love / and only fools / Would fail / to scale / your victory.

And my father was taken away shortly after that, with Norbert. They were taken to Mauthausen, to another unspeakable place. And my father was killed just weeks before the end of the war. My next camp was Auschwitz. My sister and I were taken to Auschwitz. And Auschwitz, I think, is probably the most notorious of all death factories.

The smell of Auschwitz is something that I will never forget, especially when I hear and read about historical revisionists, distortionists, people who claim that the Holocaust never happened. I wish it hadn't, but it did. And the smell of Auschwitz is always there to remind me. I remember Auschwitz as being very cold. I remember the selections, who is to live and who is to die.

I remember being very wet and very cold. And I remember being dismissed before we got our numbers and our heads shaved. So many people were brought in that time-- that particular day-- that they never shaved our heads or put numbers on our arms. From Auschwitz, we were taken on the death march.

Now the death march from Auschwitz has been written and discussed many, many times.

It was January 16th. We were taken on this march, about 60,000 people. Certainly not dressed for a hike in the winter. It was very cold. The roads were very slippery. We lived mostly on snow. And I remember my sister would not let me sleep because it was very easy to die in the snow. And, of course, if you died, you were left. If you could not keep up with the column or you could not march fast enough, if you were lucky, you rated a bullet. If not, you just dropped by the roadside.

And so every morning, the roads were loaded, strewn with bodies, with people who just didn't make it. And I remember just wanting to lie down and die. And, of course, my sister would always push me and poke me and drag me along. And she would not let me die. And, of course, through all the other horrors, she was always there supporting me, helping, always finding that extra piece of bread.

After many, many days, that death march for us ended. They found some cattle cars and they took us into Bergen-Belsen.

Of course, cattle cars are a whole other universe, too. These cattle cars were open so we were covered with snow and we lived, literally, on snow. Also, occasionally, going through Czechoslovakia, I remember there were some brave Christian farmers who would throw potatoes-- raw potatoes-- into the cattle car.

And I usually talk about that because there was so much horror, so much collaboration among the native populations, especially in Poland, that I like to point out that there were some brave people who occasionally saved a Jewish child or even a family. And, of course, those we call the Righteous Among the Nations. They are indeed.

Well, they took us into Bergen-Belsen. I think Bergen-Belsen was worse than Auschwitz. Bergen-Belsen was a death trap. There was no food. There were no blankets. There were no bunks. And the only food we ever got was we would sneak behind the German kitchens to steal whatever they threw away. Had we been caught, we would have been shot.

It was truly a death trap and typhus was the killer. Everybody in Bergen-Belsen had typhus. And we were all beginning to die. Then suddenly one day, they decided to select 30 women to go to another camp-- to a work camp, slave labor camp. And there were maybe 1,600 of those around the countries, Germany, Austria, Poland, and France and others. And somehow, my sister and I were among the 30 people who were taken to this other camp.

Again, we were put into cattle cars. This time my sister was already sick with typhus and dying. And I remember growing up very quickly because there wasn't a thing I could do for her. She was really dying and I was totally helpless. Once I caught some rainwater for her. After many days of that horror, we got into the small camp.

The camp was called Venusberg. It was run by SS women who were very brutal, very cruel. In fact, I got my one and only physical beating from this woman because I got into line for food and my sister, who was very sick, could not stand in line, so I gave her my bowl. And I got in line again, even in that "good" quote-unquote camp, we were starving. And I was very hungry but when I got in line the second time, this particular, monstrous, big SS woman recognized that it was my second time and she beat me up. And so I never got my second bowl of soup.

There were many other instances there that were really of horror. We also worked very hard. We worked making airplanes for the German Reich at Messerschmitt. And by then, there were some prisoners of war in that factory. We were not allowed to communicate with them, of course, but through the grapevine we would hear that it was almost over, just hang in there and the war will be over. And we tried. We tried to hang in there.

And I got very sick with typhus. And typhus is a very debilitating disease. You have a very high fever, throwing up, diarrhea, very thirsty. And certainly, we had no medical care whatsoever. I was thrown into this barrack for the sick from which very few people returned. And when they decided to evacuate that camp, too, they would have probably-- or I'm sure they did-- burned that barrack with all those people who were too far gone. My sister and another friend dragged me out of there.

Again, we were put into cattle cars, my very last trip. Those cattle cars took 16 days. Sealed, very hot. And perhaps it was the temperature of maybe 105, 106, whatever I had at the time. I was mostly delirious, mostly, totally unconscious. I do remember instances when they would open the sealed doors and my sister would prop me up against the back of the car and she would pinch my cheeks and make me sit up somewhat straight so that I would not be thrown out with the corpses.

And that's how we made it through the 16 days of horror. We got into Mauthausen. Mauthausen was the camp where my father and Norbert were taken. The camp where Norbert survived, where my father was killed just weeks before the end. And I remember very little except being very, very sick. We were six on a bunk like sardines. And I remember one day, I looked up and there was a black soldier, a black American soldier.

You see, the Allies, of course, knew what was happening to us by 1942. Unfortunately, we were not a priority. In fact, they refused to bomb the railroad tracks which took the victims to Auschwitz. And so the leadership of the Allies knew what was happening. The soldiers didn't. And this particular black soldier that I remember was standing there totally devastated. The horror on his face is something that, even in my state, I cannot ever forget.

And I was unable to really distinguish between nightmare and reality. I weighed about 60 pounds and I was really more dead than alive. I have one memory of that soldier and I will conclude my presentation with this poem which I call "The Black Messiah."

A black GI stood by the door / (I never saw a black before.) / He'll set me free before I die, / I thought, he must be the Messiah. / A black Messiah came for me... / He stared with eyes that didn't see, / He never heard a single word / Which hung absurd upon my tongue. /

And then he simply froze in place / The shock, the horror on his face, / He didn't weep, he didn't cry / But deep within his gentle eyes / ...A flood of devastating pain, / his innocence forever slain. / For me, with yet another dawn / I found my black Messiah gone / And on we went our separate ways / For many years without a trace. / But there's a special bond we share / Which has grown strong because we dare / To live, to hope, to smile... and yet, / We vow not ever to forget.

Remembering the Past: Sonia Weitz’s History

Sonia Weitz speaks about her experiences before and during the Holocaust.

I, too, was a child when the Nazis invaded Poland in 1939. My six years of darkness include the Krakow Ghetto, Plaszow, Auschwitz, the death march, cattle cars, Bergen-Belsen, and finally Mauthausen.

You see, when I was a little girl, the world was comprised of two kinds of nations-- those that would not allow the Jews out and those that would not allow the Jews in. Immigration requirements were impossible. And there was no Israel. And so we were trapped, and we were slaughtered. For me, the devastation was complete. My mother was killed in the death camp in Belzec, my father in Mauthausen. Out of a family of 84, only my sister Blanca and I survived.

Mark suggested that each of us share a vivid memory. And boy, did I struggle with that, because most of my memories, especially the bad ones, are very, very vivid. And I decided on a memory from Bergen-Belsen, which I believe was worse than Auschwitz. And some of this unspeakable horror is depicted-- again, I'm forever leaning on my poetry. It's depicted in the poem I call "Icicles."

But let me explain. Bergen-Belsen was a death trap. There was no work. There were no-- the barracks-- 400 women in a barracks that was meant for 40, maybe. No blankets, no bunks. We were not fed in that camp at all, because we didn't work. And so the only food we ever had was something we would manage to steal, going behind the German kitchens. Of course, if you were caught, you were shot.

And so I remember endless hours in that camp, standing on the roll calls. And very little has is being said about the appellplatz, the horror of standing there, sometimes for 14 hours. And so numbed beyond pain, I very often fantasized, and I wrote poems in my head. And this poem is called "Icicles."

The wind is brutal. The rain, icy cold. I shiver and hold out my empty fists. My stomach twists with hollow cramps. The hunger, not unbearable. It dulls my wits and sets my mind aswim. My vision dims most pleasantly. I tremble. I weep. And quite detached, I watch myself. Am I asleep? Or do I now belong among the dead?

And yet, I know I am alive. I know because along my bony cheek, a tear escapes. It quickly turns to ice. How nice. How nice to remember, to see. I see icicles and me. A little girl, a window sill, and frost upon the pane. And down the lane, a friend. My mother's voice, the smell of food. My father's laughter fills the air.

I sigh. I stare. The wind has chased my dream away and left but emptiness. The icicles now burn my lips. They turn to salt. It's true. There are no bitter tears, 'cause tears and blood, sweat, too, they all taste salty, tart. And bitterness? Ah, bitterness. That dwells within my heart.

I am cold, hungry, I hurt. Does anyone know I am here? Does anyone care?

Thank you.

[APPLAUSE]

Sonia Weitz Remembers the Holocaust and Recites Her Poem Icicles

Sonia Schreiber Weitz, Holocaust survivor, remembers the brutality of Bergen-Belsen.

Danger in Forgetting: Eyewitnesses to the Holocaust: Sonia Weitz

This documentary looks at the struggles of Holocaust victims through their own eyes.

Explore Photographs

Learn more about Sonia Weitz’s life through this collection of personal photographs.

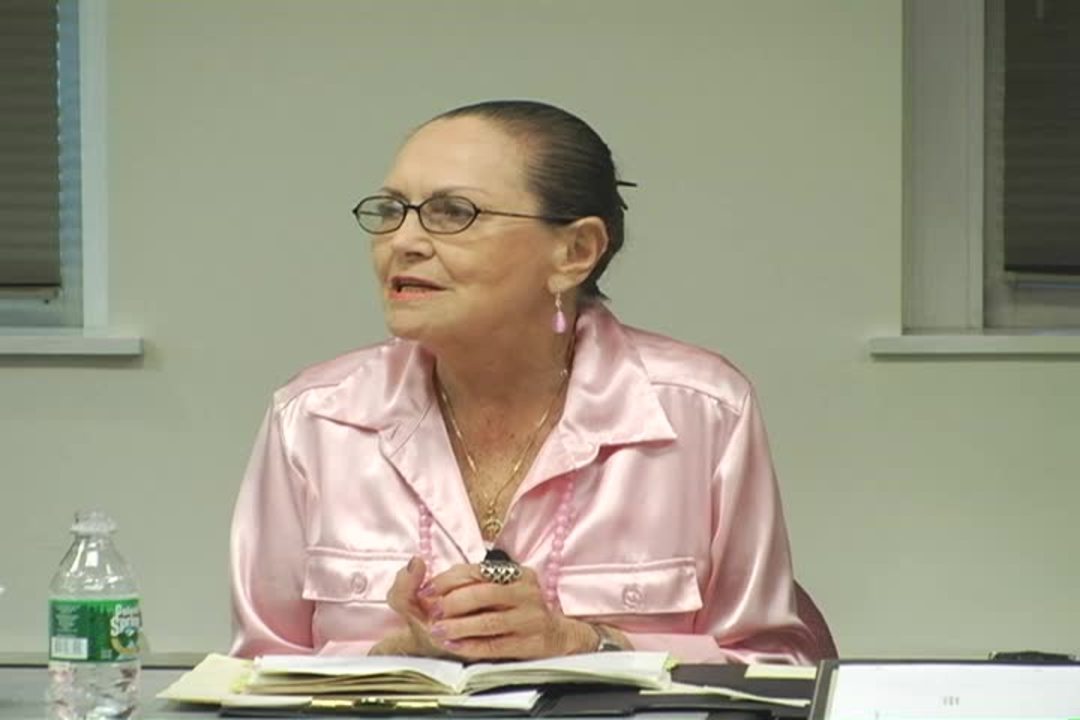

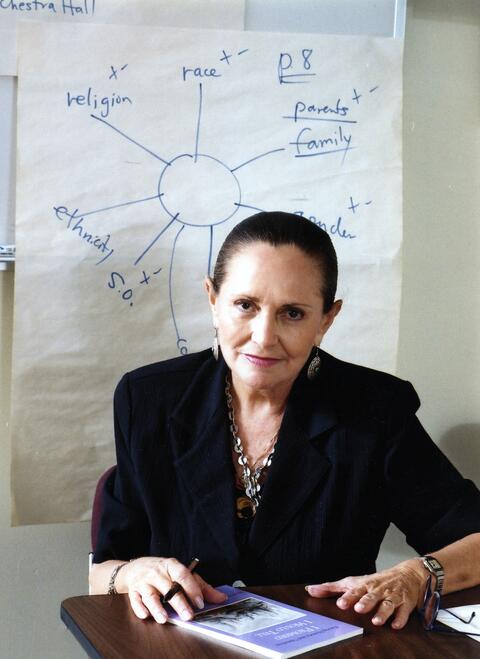

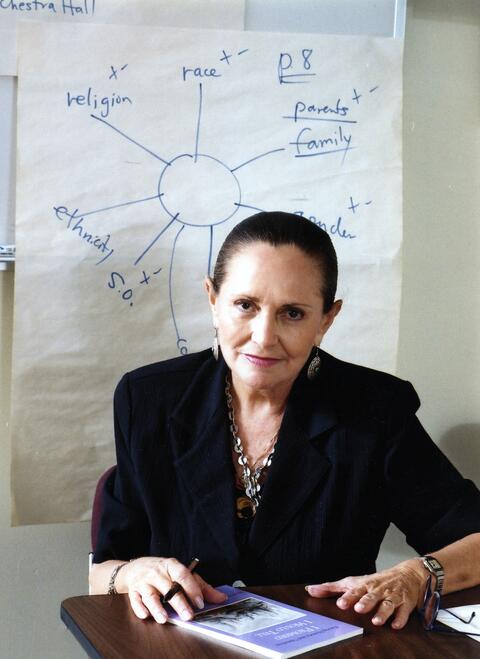

Sonia Weitz

Sonia has dedicated her life to telling her story in the hopes of teaching young people about the dangers of being a bystander. Through her organization, the Holocaust Center: Boston North, Sonia has reached out to survivors from other genocides to gain a greater understanding of human behavior, and to create a stronger community of people committed to preventing future genocides.

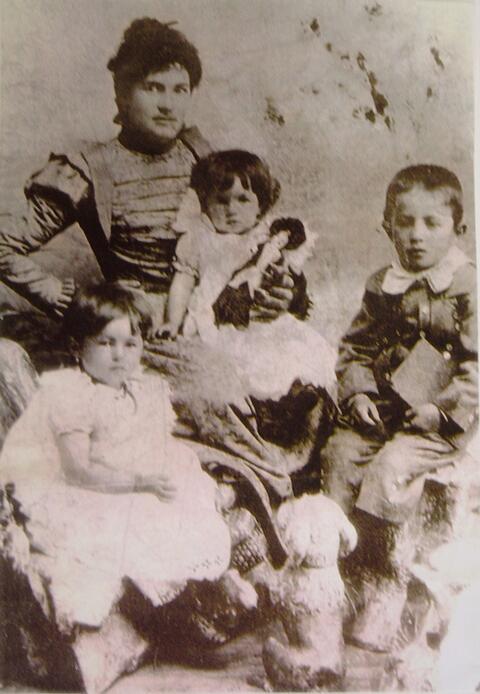

Rachel Finder, Sonia’s Grandmother, with Children

Rachel Finde was one of many children and was sent away to be raised by distant relatives. When she was fourteen, Rachel's foster mother died, and Rachel married her foster father. The family was wealthy, but Rachel was abused by her husband. When he passed away, Rachel inherited all of his belongings, including a farm. Being the only Jewish woman farmer in her community, she earned the respect of the nearby farmers. Rachel remarried and had six children; two daughters (one of whom was Sonia's mother, Adela, seated in front in this photo) and four sons. One of the sons was adventurous and left for South Africa before World War II. Although leaving Poland saved him from perishing in the Holocaust, the guilt he felt for abandoning his family would eventually cause him to lose his mind. During the winters, Rachel would often travel to Krakow to be with her family. Sonia remembers her grandmother knitting. During the summers, Rachel always had one of her grandchildren stay with her.

Adela Finder Schreiber, Sonia’s Mother

Adela was a farm girl who fell in love with a city businessman. She lived in Kraków and had three children. Blanca was the oldest and Sonia was the youngest. The middle child, Stella, died of diphtheria.

Sonia’s Cousin, Vitek

Sonia Weitz's cousin, Vitek (middle) Vitek was the son of Sonia Weitz’s Uncle Henek, the first person in the family to be killed. Vitek managed to escape the ghetto with his mother, though they were both eventually killed in Auschwitz.

Norbert Borell, Blanca's Husband

Norbert married Sonia’s older sister, Blanca, in the early stages of the Holocaust. Both he and Blanca survived Nazi rule, and he remained married to her for the rest of his life. As Blanca served as a mother figure to Sonia, Norbert served as a father figure. He always pushed her to keep studying. Norbert was a dedicated activist, but he still took the time to be a dedicated family man.

Sonia’s Sister, Blanca Borell

Blanca Borelll is Sonia Weitz's older sister, the only other member of Sonia's family who survived the Holocaust. After the death of their parents, Blanca fulfilled the role of sister and mother to Sonia. Sonia credits Blanca with essentially raising her to be the woman she is today. Blanca and Sonia remained very close throughout their lives.

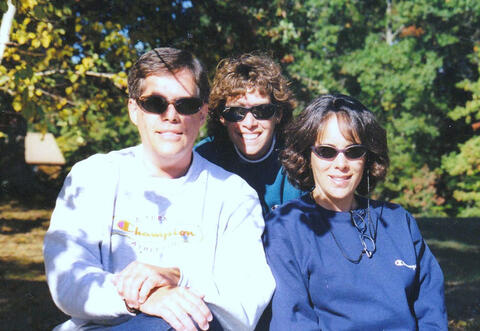

Blanca and Norbert Borell, and Sonia Weitz, 1947

Blanca was like a mother to Sonia and tried to bring normalcy to her life in the aftermath of the intense trauma they experienced during the Holocaust. Sonia was a feisty teen when the war ended and it was Blanca and her husband, Norbert, who insisted that Sonia study, hiring tutors for her in every subject. Sonia would have rather been out riding motorcycles with the American GI's!

Sonia Weitz and Rena Finder

Sonia and Rena met when they were children in Poland and were in the Krakow ghetto together. Rena and her mother were fortunate to have been chosen to be on Schindlers list . Sonia was sent on to Auschwitz , Bergen Belsen, Venusberg and then Mauthausen. The two best friends reconnected after the war in a DP (Displaced Persons) camp and came to the United States together, sponsored by Sonia's uncle. Rena and Sonia remained friends throughout their lives.

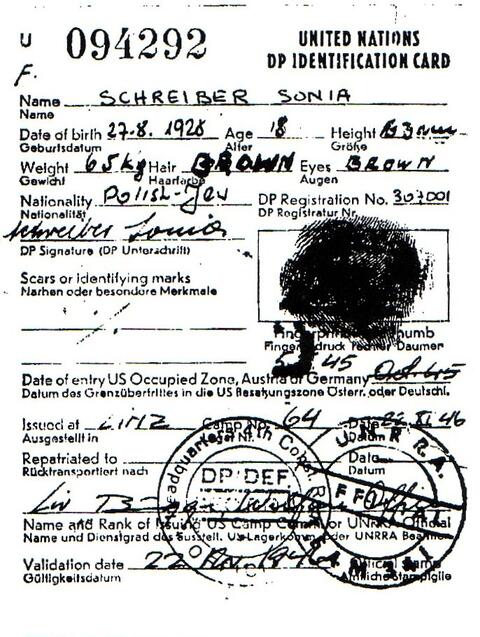

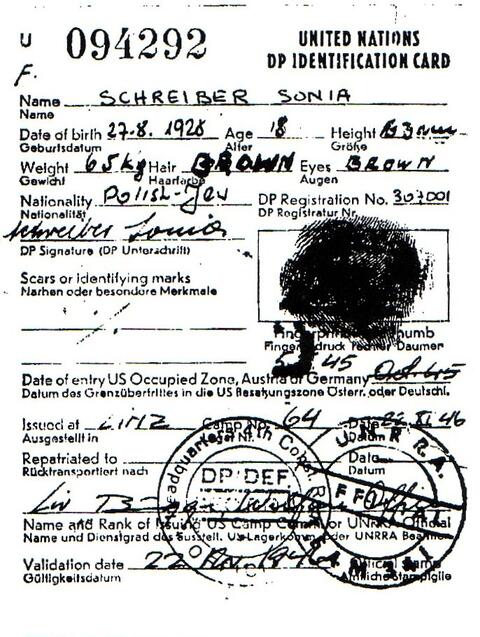

Sonia’s Identity Card from the DP camp

After the camps were liberated the Jews were sent to Displaced Persons (DP) camps. Sonia Weitz stayed in Linz , Austria at the Bindermichl DP camp. At these camps, Jews were able to regain their birth name and start the journey to a new life.

Sonia in DP camp, 1946

After enduring the horrors of the Holocaust, knitting was something that brought a sense of normalcy to Sonia Weitz's life. The radio in the background was given to her by an American GI. Back in 1946, having a radio was a luxury! Sonia remembers writing and knitting as her two core hobbies.

Explore Photographs

Learn more about Sonia Weitz’s life through this collection of personal photographs.

Sonia’s Ring

This special ring was given to Sonia on her 17th birthday by her brother-in-law, Norbert Borell. As Sonia writes, the ring had "once belonged to a young [Jewish] man who kept poison in its hollowed dome. The young man apparently intended to take his own life at the 'right moment'...Sadly, he never got the chance to take his own life. The Nazis beat him to it" (p. 77, "I Promised I Would Tell" ). Norbert came into possession of the ring because he had been a friend of the victim, whose family had all been killed during the Holocaust. Norbert gave Sonia the ring because according to Sonia, he "thought that I was a self-centered teenager and hoped the ring would make me remember and care." It remains a precious gift to this day.

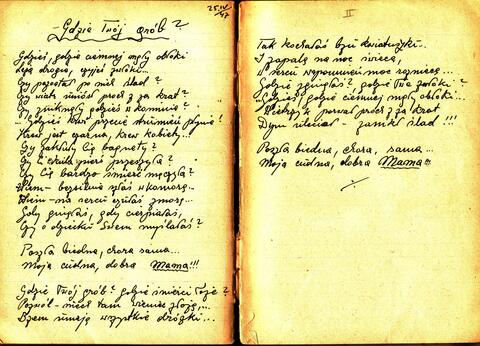

Sonia Writing Poetry, 1945

Sonia used to hide in the Strahl's apartment to write poetry while in the DP camp at Bindermichl. Poetry was a release for her when she was overwhelmed by her feelings. Portions of her reconstructed diary, in Polish, were later translated and then edited and published by Facing History as " I Promised I Would Tell."

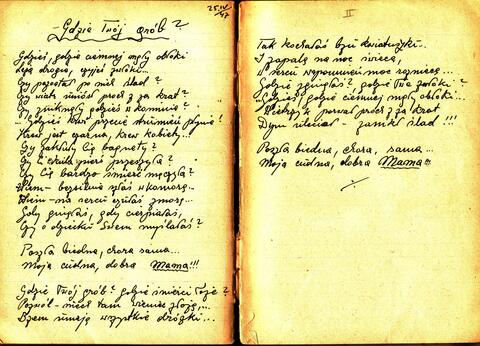

Sonia’s Poem "To My Mother”

Sonia spent three years in Displaced Persons (DP) camps. It was there that she wrote many of her poems. This is her original poem, written in Polish, "To My Mother." This poem is studied by students all over the world who find its universal message of loss so compelling.

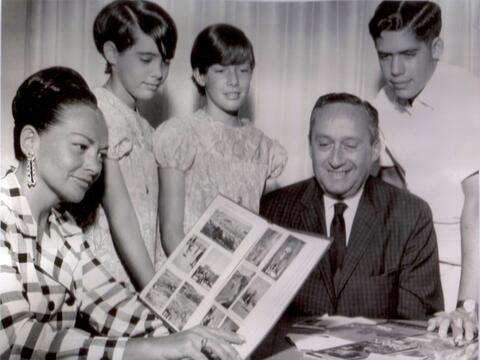

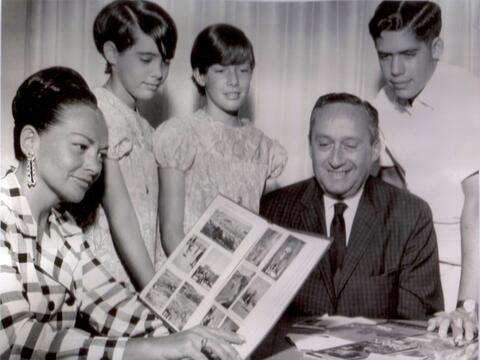

Sonia Weitz, Norbert Borell, and Friends, 1948

This photo was taken in the DP Camp in Bindermichl. Sonia Weitz poses with some American reps of HAIS and her brother-in-law, Norbert Borell. Norbert, always an activist, worked for the resettlement organization "HIAS." He asked Sonia to help. This was a political awakening for Sonia. She learned how to manipulate the system and advocate on behalf of their survivors. If a town needed a farmer, she would tell her client " you are a farmer now." They helped many people get a chance at a new life.

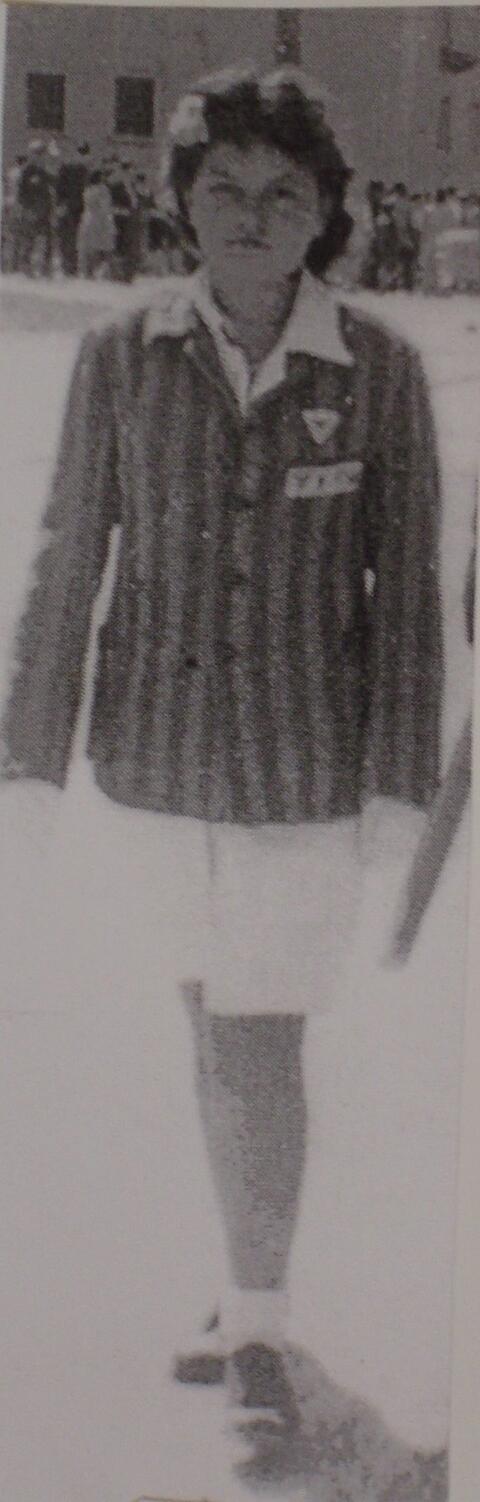

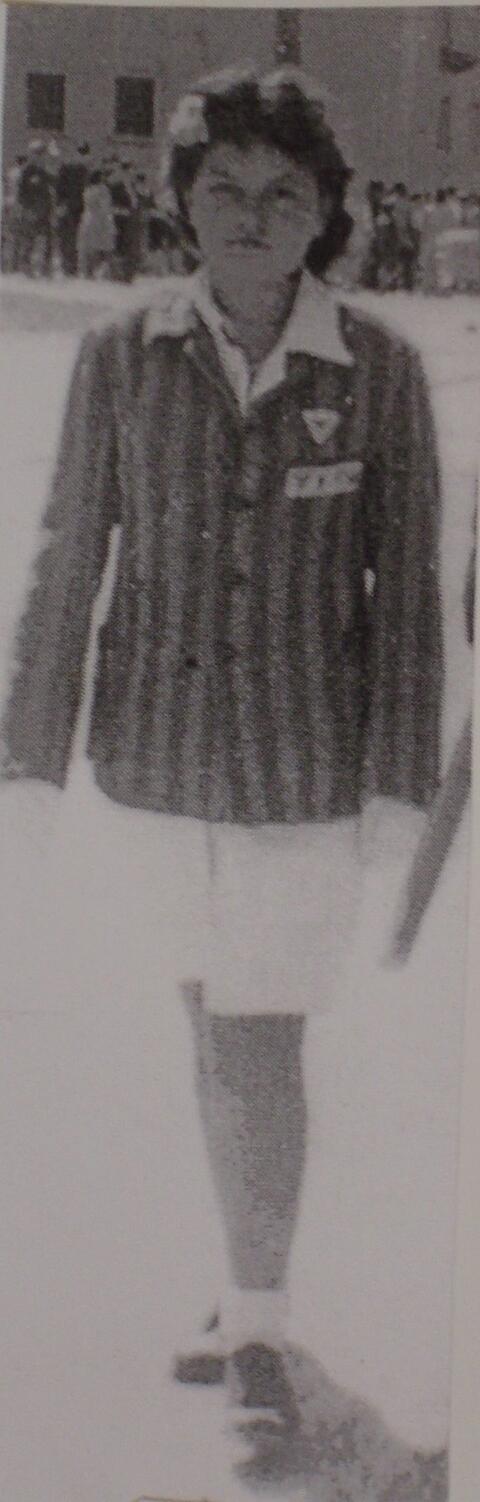

Sonia in Uniform, 1946

This photo is of Sonia Weitz protesting at a rally to remain on the farm that she lived on in a DP camp in Lintz. The Austrian government demanded that Sonia give back the farm and return to Mauthausen. They received help from American GI’s, who helped make posters and write speeches. They won and were permitted to stay on the farm. This is one of the first times Sonia took up political activism and fought the government.

Harry White Peabody, 1948

Harry White was Norbert Borell’s (Blanca's husband) uncle. He brought Sonia, Blanca, Norbert, Rena and her husband Marc to Peabody from Europe.

Sonia after the War

The experience at the camps made Sonia yearn to have long hair again. She recalls her joy in combing and caring for her hair as if that alone could erase some of the memories of the camps.

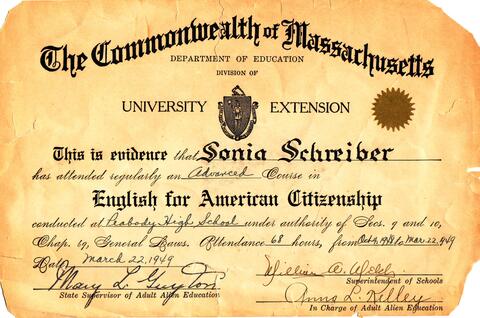

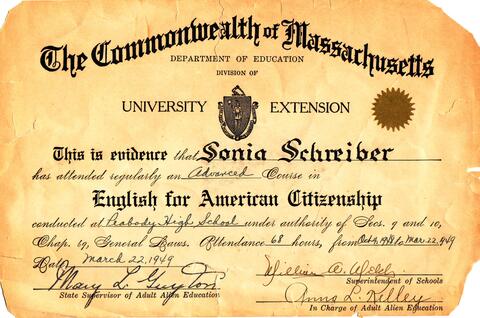

Sonia’s English Certificate for American Citizenship

Sonia became an American citizen in 1949. She has lived in Peabody her entire life since she came to the United States. Sonia was awarded this certificate after completing an advanced course in the English language under the U.S. Department of Education.

Sonia and Mark Weitz's Wedding, 1950

Mark Weitz was a physician who served in the medical corps of the US army during World War II. He suffered a head injury at Normandy and was sent to an English hospital. In 1948 he moved to Peabody, Massachusetts to practice medicine. Mark was on a house call when he met Sonia. It was a fast courtship and soon they were married! Mark and Sonia had three children and they were together for nearly fifty years when Mark died. Sonia spent her time writing poetry and pursuing causes focused on protecting human rights. Mark recognized the importance of her speaking in public and working with survivors.

Sonia Weitz, 1951

This photo of Sonia was taken on her and Mark's first wedding anniversary in 1951. Mark always gave Sonia Gardenias on their anniversary.

Explore Photographs

Learn more about Sonia Weitz’s life through this collection of personal photographs.

Sonia and Mark’s Family

Sonia, Mark, Andi, Sandy, and Don lived in Peabody, Massachusetts. Sonia became a human rights activist and opened the Holocaust Center North, in Peabody, to educate the neighboring communities about the lessons of the Holocaust and to preserve the memories of survivors. Her work has become known internationally. In 2002 Sonia was appointed to the Council of the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum. When Sonia asked how the museum found her, they told her that a student intern at the museum had heard her speak at a school in Massachusetts and was struck by her words. This family photo from 1967 was taken when Mark and Sonia had returned from a trip to Israel just after the Six Day War.

Sonia Weitz and Blanca Borell, 1965

This photo of Sonia and Blanca was taken on New Year's eve, 1965.

Sonia Weitz, 1960

Sonia Weitz and Blanca Borell, 1960

Sonia Weitz and her sister, Blanca Borell, remained close throughout their lives. They were the only two members of their family to survive. They moved out of Europe and came to live in Peabody, Massachusetts with Norbert, Blanca's husband.

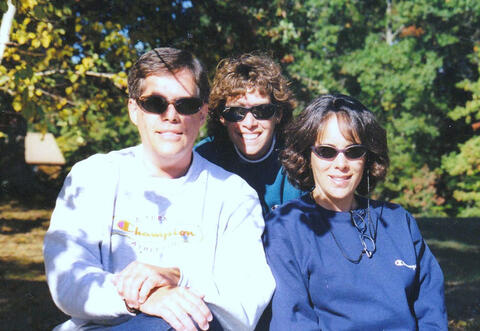

Sonia’s Children

Sonia's children, Don, Sandy and Andi.

Tree Planted by Sonia Weitz's father, Krakow, 1986

Photographed in Krakow in 1986, this tree was planted by Sonia Weitz's father on the day she was born. It is the subject of her poem, "The Tree of Life."

Related Resources

I Promised I Would Tell

You might also be interested in…

Americans and the Holocaust: The Refugee Crisis

Teaching the Holocaust and Armenian Genocide: For California Educators

Introducing and Dissecting the Writing Prompt

Introducing Evidence Logs

Telling Our Histories

Adding to Evidence Logs, 1 of 4

Adding to Evidence Logs, 2 of 4

Adding to Evidence Logs, 3 of 4

Watching Who Will Write Our History

Adding to Evidence Logs, 4 of 4

Refining the Thesis and Finalizing Evidence Logs

Teaching Who Will Write Our History