We the People in the United States

At a Glance

Language

English — USSubject

- Civics & Citizenship

- History

- Human & Civil Rights

- The Holocaust

In 1787, 11 years after the Declaration of Independence proclaimed that “all men are created equal,” the US Constitution was adopted. It begins with this preamble:

We the People of the United States, in Order to form a more perfect Union, establish Justice, insure domestic Tranquility, provide for the common defence, promote the general Welfare, and secure the Blessings of Liberty to ourselves and our Posterity, do ordain and establish this Constitution for the United States of America. 1

Who is included in “We the People”? This is a question that has been debated throughout American history. William H. Hastie, the first black federal judge in the United States (appointed in 1937), wrote: “Democracy is a process, not a static condition. It is becoming, rather than being. It can be easily lost, but is never finally won.” Much of the history of the United States reflects this ongoing process, as individuals and groups have attempted to make the country better reflect the democratic ideals expressed in its founding documents.

Women’s suffrage activist Susan B. Anthony was one individual who challenged the country to expand its definition of who belongs. In November 1872, she was arrested for voting in a federal election before women had gained the right to do so. Before her trial, she gave a speech titled “Is It a Crime for a Citizen of the United States to Vote?” In that speech, she quoted the preamble to the Constitution and then stated:

It was we, the people, not we, the white male citizens, nor yet, we, the male citizens; but we, the whole people, who formed the Union. And we formed it, not to give the blessings of liberty, but to secure them; not to the half of ourselves and the half of our posterity, but to the whole people—women as well as men. And it is a downright mockery to talk to women of their enjoyment of the blessings of liberty while they are denied the use of the only means of securing them provided by this democratic-republican government—the ballot. 2

To support her argument, Anthony pointed out that “the words persons, people, inhabitants, electors, citizens are all used indiscriminately in the national and state constitutions.” In some states, only white men could vote; in others the language was vague enough that all property owners, including white women and African Americans, could vote. Yet, by the early 1800s, white men no longer needed to own property or pay taxes in order to vote anywhere in the United States. At the same time, states that had previously allowed free African Americans and women to vote now took away those rights.

In 1776, Virginia, South Carolina, and Georgia were the only states to limit the right to vote to white men, and no northern state limited suffrage on the basis of skin color or race. After 1800, every state that entered the Union, except Maine, denied free African American men the right to vote.

In a nation that declared its belief in freedom and equality, those decisions had to be justified. And for many, there was only one justification: Native Americans and blacks belonged to distinct and inferior “races” and therefore should be denied full citizenship. In 1857, the US Supreme Court confirmed that view. The justices heard a lawsuit brought by Dred Scott, an African American who demanded his freedom because his “owners” had taken him to several states and territories that did not permit slavery. In a decision written by Chief Justice Roger B. Taney, the court ruled that blacks “had no rights which the white man was bound to respect.” The American people, Taney argued, constituted a “political family” restricted to whites.

By 1865, a brutal civil war had finally brought an end to slavery in the United States but not to the prejudice and the discrimination experienced by African Americans. Immediately after the war, three amendments were added to the US Constitution to protect African Americans’ rights—the thirteenth amendment ended slavery and the fifteenth granted former slaves the right to vote, but it was the fourteenth that Susan B. Anthony focused on in her 1872 speech. That amendment states, in part:

All persons born or naturalized in the United States, and subject to the jurisdiction thereof, are citizens of the United States and of the State wherein they reside. No State shall make or enforce any law which shall abridge the privileges or immunities of citizens of the United States; nor shall any State deprive any person of life, liberty, or property, without due process of law; nor deny to any person within its jurisdiction the equal protection of the laws. 3

Susan B. Anthony saw those two sentences as proof that women had all of the rights of citizenship. In her view, the first sentence established that women are citizens, and the second settled whether or not they hold a place in society equal to that of all other “persons.” She concluded her speech by firmly stating:

The only question to be settled, now, is: Are women persons? And I hardly believe any of our opponents will have the hardihood to say they are not. Being persons, then, women are citizens, and no state has a right to make any new law, or to enforce any old law, that shall abridge their privileges or immunities. Hence, every discrimination against women in the constitutions and laws of the several states, is today null and void, precisely as is every one against Negroes. 4

Despite her argument, Anthony was tried and convicted for “the crime of having voted” in the 1872 election and fined $100. Women did not obtain the right to vote in the United States until 1920. In fact, until 1922, a woman born and reared in the United States would lose her citizenship if she married a foreigner. She had to assume the citizenship of her husband. However, an American man could marry a foreign woman without losing his citizenship.

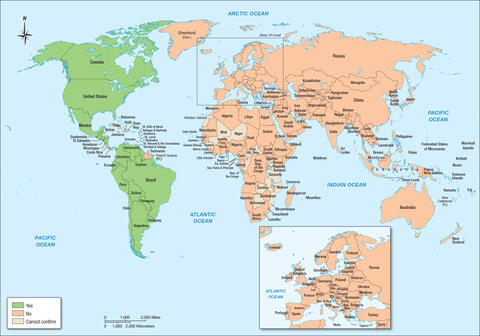

Even though the fourteenth amendment introduced birthright citizenship—meaning that anyone born within a country’s borders is automatically a citizen regardless of the parents’ nationality—this remains a controversial idea, both in the United States and in other countries. The extent to which the amendment’s promise of “equal protection of the law” is a reality continues to be debated today. In 2010, about 15% of the countries in the world, nearly all of them in North or South America, recognized birthright citizenship (see map below). 5

- 1U.S. Const. preamble, available at the National Constitution Center website.

- 2Susan B. Anthony, "Is It a Crime for a Citizen of the United States to Vote?" (1872), quoted in Speeches that Changed the World (London: Quercus, 2005), 43.

- 3U.S. Const. amend. XIV, available at the National Constitution Center website.

- 4Susan B. Anthony, "Is It a Crime for a Citizen of the United States to Vote?" (1872), quoted in Speeches that Changed the World (London: Quercus, 2005), 43–44.

- 5Eyder Peralta, “3 Things You Should Know About Birthright Citizenship,” The Two-Way (blog), NPR, August 18, 2015.

Susan B. Anthony, 1870

Susan B. Anthony, 1870

Women's suffrage leader Susan B. Anthony on her 50th birthday.

Birthright Citizenship Worldwide (2015)

Birthright Citizenship Worldwide (2015)

Who can be a citizen? Many countries recognize birthright citizenship, meaning that anyone born within a country's territory is automatically a citizen, even if the parents are not citizens.

Connection Questions

- Who did the phrase “We the People of the United States” refer to when it was written in 1787? What did the preamble to the Constitution promise to those people?

- What are the benefits and responsibilities of citizenship in a country? How did America’s leaders justify excluding women, African Americans, and Native Americans from the benefits of citizenship?

- What options are available to individuals when their nation does not live up to its ideals? How did Susan B. Anthony confront the differences she experienced between ideals and reality in the United States and work for change?

- What is a democracy? How is it different from other forms of government? How should a democratic society define its universe of obligation?

How to Cite This Reading

Facing History & Ourselves, "We the People in the United States," last updated August 2, 2016.